Heading towards Phnom Penh “If Vietnamese soldiers had come late, Cambodians would die all"

Volunteer Vietnamese soldiers in Cambodia (Photo: VNA)

Volunteer Vietnamese soldiers in Cambodia (Photo: VNA)

Hanoi (VNA) - Villages were burned and abandoned. Human bones piled up in bomb craters. Dirty, skinny, naked Cambodian kids were begging for food on the streets.

Such miserable images in Cambodia during 1978-1979 are still fresh in the mind of soldiers. The country would have become a mass grave if the Vietnamese soldiers had arrived too late.

Meals offered by soldiers, and clothes made from parachute dead poncho

In early 1979, Colonel Huynh Tri (former head of the political department of the Military Command of An Giang province, and Hero of the People’s Armed Forces) and his comrades marched towards Cambodia in an effort to help the neighbouring country get out of the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime. The 69-year-old veteran vividly remembers his battlefield stories.

Staying silent for a while, he said what haunted him while in Cambodia was not the battles but the miseries of locals.

Colonel Huynh Tri, former head of the political department of the Military Command of An Giang province, and Hero of the People’s Armed Forces (Photo: VietnamPlus)

Colonel Huynh Tri, former head of the political department of the Military Command of An Giang province, and Hero of the People’s Armed Forces (Photo: VietnamPlus)Tri’s battalion joined Division 9905 to depart from Frontline 779 in the southwestern border province of An Giang, heading towards Phnom Penh to chase Pol Pot’s troops. During their march from the border area to Cambodia, Vietnamese soldiers passed through burned and abandoned villages. Houses and pagodas were destroyed, with decapitated Buddha statues. There were no signs of life in the villages and hamlets.

Marching further, Tri met a dying old man on a roadside, with his ribs seen through his pale skin.

“When seeing Vietnamese soldiers, the man said he had been hunted by Pol Pot’s troops and run away. However, he had collapsed because of hunger,” Tri said.

None of the man’s relatives could escape the troops. They were all buried in a mass grave deep in a rubber forest next to their village. The hungry man was crying while eating packed food portion offered by Vietnamese soldiers, saying he hadn’t eaten good food for years.

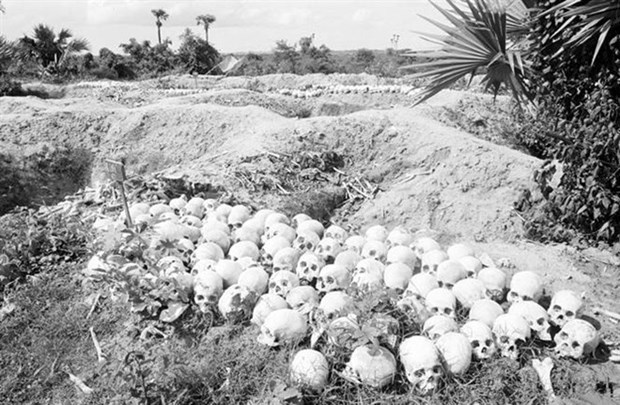

Mass graves of innocent people killed by the Pol Pot genocidal regime are discovered after January 7, 1979 at the “Killing Fields” in Choeung Ek, Cambodia. (Photo: VNA)

Mass graves of innocent people killed by the Pol Pot genocidal regime are discovered after January 7, 1979 at the “Killing Fields” in Choeung Ek, Cambodia. (Photo: VNA)Hunger and thirst struck all Cambodian villages at that time. Tri recalled: “Once we found a village where the people were still living. We were welcomed by all of more than 200 villagers. They looked miserable, hungry and poor after a long time of working as slaves. Most of them dressed in rags and or even not clothes. They cried while holding our hands and said: ‘Don’t go, please. If you go, Pol Pot’s troops will kill all of us. Please let us go with you’.”

That day, the villagers scooped up three bowls of rice from the bottom of their jars to prepare a meal for the whole battalion. Tri could not hold back his tears when seeing rice grains that were turning brown due to mould. He asked for permission to cook rice and food to aid the villagers. A large rice pot was put in the middle of the village yard for the villagers. Vietnamese soldiers made tea and delivered packed food portions and candies to them. The dying village was in a festive atmosphere after a few minutes.

Years after the war ended, Hai Tri can still remember what one village elder said: “Over the past five years, locals have not eaten their fill or had a sip of tea.”

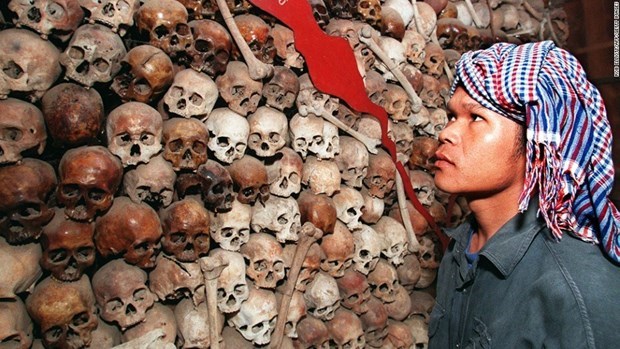

A Cambodian lady stands next to a wall of skulls of victims of the Pol Pot genocidal regime at Tuol Sleng Museum. (Source: Getty images)

A Cambodian lady stands next to a wall of skulls of victims of the Pol Pot genocidal regime at Tuol Sleng Museum. (Source: Getty images)Food and clothing was a far-reaching dream of Cambodians at that time.

Tri said he and his comrades were astonished by Cambodians in dresses made from parachutes used by Vietnamese. The locals said they dug up graves of Vietnamese soldiers to search for the fabric that could be made into clothes.

In the eyes of locals, Pol Pol was a monster that left hunger, thirst, death and misery in villages.

Corpse-filled wells and the revival in the dead land

Tran Dang Truong, a former soldier, still remembers the wells stuffed with dead bodies he saw while marching towards Cambodia.

Looking far away, he said with a sad voice: “In 1977, when we were students, we were encouraged to participate in the struggle to protect Vietnam’s southwestern border and the fight against the Pol Pot genocidal regime. I joined Battalion 86, Regiment 132 of the Information High Command.”

When reaching Siem Reap, the young soldiers were shocked by dead cities where corpses scattered roads.

“The cities were deserted, without even rooster crowing sounds. What was left was wild grass. Pol Pot’s troops robbed all, burned all and killed all,” he said.

The most horrific things were the wells stuffed with dead bodies. The deep, bomb crater-sized holes with clear water reminded the soldiers of rivers, so they would jump in for a bath. However, when reaching the bottom, they were panicked seeing human bones and swam upwards. At the sight of the piles of broken bones, the young soldiers, who had been always optimistic, even amid storms of bombs and bullets, and never been afraid of death, shivered with fear and vomited.

A mass grave under the Pol Pot genocial regime (Source: Getty Images)

A mass grave under the Pol Pot genocial regime (Source: Getty Images)“We felt like there was hell beneath our feet. Two of my comrades suffered from uncontrollable diarrhoea due to the water of the hole, and they were sent back to Long An province for emergency aid. Such holes became our obsession during the march,” Truong said.

What’s more, soldiers went to the forest to search for mice as food. However, their face turned pale when seeing piles of human bones inside the mouse holes.

“It was a real hell as humans became meals of animals,” Truong said with a sigh.

After Phom Penh was liberated, survivors returned to their hometowns with scarred, bare feet and iron rims of bicycles that were worth a fortune.

Cambodia's revolutionary armed forces and Vietnamese volunteer soldiers in a joint exercise (Photo: VNA)

Cambodia's revolutionary armed forces and Vietnamese volunteer soldiers in a joint exercise (Photo: VNA)With a rare smile when recalling the past, the former soldier said: “That day, just after the liberation, I and my comrades went through a derelict mango orchard. We could not resist the mango on the sunny day. A thin old man came to us.”

“Xom nham bai,” a Vietnamese soldier spoke Khmer to invite the old man to join them.

The man enjoyed mango with the Vietnamese soldiers. When asked in Vietnamese about the owner of the mango orchard, the man replied: “It is my family’s. But please feel free to eat as other family members were killed by Pol Pot’s troops. I survived as I fled to Vietnam. Please enjoy the mango and bring some for your comrades.”

Another time, his battalion marched to a liberated village. Almost immediately, villagers rushed to welcome them. Among the villagers, an old lady kept bowing to the Vietnamese soldiers and said: “Thank you. If you did not come, all of my family would be buried in the mass grave.”

For soldiers like Truong, such reactions were more valuable than anything else as they show the respect and feelings of Cambodians towards Vietnamese soldiers.

Vietnamse volunteer soldiers and Cambodians (Photo: VNA)

Vietnamse volunteer soldiers and Cambodians (Photo: VNA) Thanks to efforts of Vietnamese soldiers like Tri and Truong, the Khmer Rouge regime was overthrown and driven from Phnom Penh; marking the destruction of one of the most devastating genocidal regimes in human history. Since then, the seeds of peace and happiness started sprouting in Cambodia.-VNA