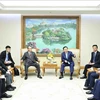

In the family: Hien (left) and Tilo have nurtured their happiness at the centre (Courtesy Photo of the family)

In the family: Hien (left) and Tilo have nurtured their happiness at the centre (Courtesy Photo of the family) Ninh Binh (VNA) - The Endangered Primate Rescue Centre in the Cuc Phuong National Park is run by enthusiastic experts who have overcome many problems over the past 20 years.

A bright morning and the sun sends fragile rays through layers of leaves in Cuc Phuong National Park in the northern province of Ninh Binh. The twittering of birds and chattering monkeys is a natural alarm for staff at the Endangered Primate Rescue Centre (EPRC).

Two attendants slowly walk on the path between the trees and cages of primates that need special cares. They talk about the monkeys they put geographical positioning rings on. They will release them back into the wild in few days.

For the past 20 years, Nguyen Thi Thu Hien and Tilo Nadler have enjoyed the start of each day walking round the centre.

Nadler first went to Cuc Phuong in 1991 to make a report for German TV on Delacour’s langur – one of the world’s rarest primates, which was discovered by a French expedition in 1930, based on two skins from a local hunter.

After more than 50 years without any information about this primate, in 1987 the first living individuals were seen in the national park. Nadler sent a project proposal to Frankfurt Zoological Society for conservation work and research.

In January 1993, he started the primate centre in Cuc Phuong. It was the first in Indochina.

“The first goal of the centre was to provide housing for trapped or injured primates,” he said, “This work not only help the animals, but supports the work of rangers and forest protection authorities through the whole country.”

Nadler said the knowledge about the status of many primate species in the early days was poor, the numbers of the rarest species over-estimated and the problems and survival of populations in the wild completely under-estimated.

“It was often very difficult to convince forest protection authorities and police to support conservation activities,” he said, “With correct and stricter law enforcement, the numbers of confiscations increase, requiring us to intensify fund-raising activities abroad and to hire more staff.

“With better knowledge, we recognised that several species were already on the brink of extinction. Therefore the goal of the centre concentrated not only on rescuing monkeys, but building a breeding centre to re-introduce animals back into the wild to bolster depleted wild populations or to establish a new population where they had been wiped out,” he said.

The centre runs successful breeding programmes for some of the world’s rarest primate species – the Cat Ba langur, Delacour’s langur, Grey-shanked douc langur, Hatinh langur and other highly endangered species. It now keeps 15 Vietnamese primate species, six of them survive only at the centre.

More than 200 primates have been born at the centre and reintroduction programmes carried out for Delacour’s and Ha Tinh langurs, Pygmy and Slow lorises.

The centre also carries out education programme and research activities. More than 20 Master and PhD theses are produced in co-operation with universities in Vietnam and abroad. This has led to the publication of more than 100 scientific papers.

Nadler has not only found success in preserving primates, he found his family in Vietnam as well.

With Hien, his assistant at the beginning of the project, Nadler has set up a happy family and now has two sons.

Yet their marriage has not been as easy as running the centre due to the 31-year-gap in their ages.

“My parents and relatives did not agree until my father retired and my relatives found a letter written by my grandfather predicting that I would get married to a foreigner,” Hien said.

In 2,000, they married in a simple ceremony in Dresden, Germany, following an engagement ceremony in Vietnam.

"My two sons love painting," she said. "It is a talent inherited from their father’s family. They also enjoy studying nature.

“On our holidays, we often visit forests and parks in Vietnam, Thailand and other neighbouring countries to explore nature,” she said.

Since 2016, Nadler and Hien have gradually transferred part of their tasks to other colleagues at the centre.

The centre now has 28 staff, a communications specialist, a volunteer coordinator, a foreign head keeper and one director. The main financial sources are from international organisations and zoos.

“The difference between conservation work in Germany and Vietnam is that in Germany it is funded by the government and national donors, such as companies and institutions,” said Nadler, “While in Vietnam, the biggest financial source for conservation work in Vietnam comes from abroad.

The director of the centre, Sonya Prosser, said she thought Nadler had achieved a lot. “Without his work, the Delacours langur would most probably be extinct. He had the foresight to breed the animals he rescued, where most rescue centres do not.

“This work is important for these species as it provides biologists with opportunities to study to animals, which better equips them for conserving the animals.

“It also creates a population for re-introduction into empty areas. I think the centre, under Nadler’s management provided a great source of data for researchers in many fields over its 23 years of operation,” she said.

She believes now is the time for Vietnamese people to feel a sense of ownership of the EPRC.

“Nadler has been caring for it, but it’s time for the Vietnamese people to own it,” she said, “This means taking responsibilities for what is happening to local wildlife.”

Prosser suggested the centre generate its own running costs. Leipzig Zoo is a great support, financially - and also in attempting to reach a similar vision.

“If the centre can cover its own running costs, then all additional donations or support can go directly towards education, research, re-introduction programmes. Current staff will be given opportunities to develop a career path if they desire, which in turn will grow the centre’s capacity.”-VNA

source